Home

Blog

Composers

Musicians

Black History

Audio

About Us

Links

Composers:

Adams, H. Leslie

Akpabot, Samuel Ekpe

Alberga, Eleanor

Bonds, Margaret Allison

Brouwer, Leo

Burleigh, Henry Thacker

Coleridge-Taylor, Samuel

Cunningham, Arthur

Dawson, William Levi

Dede, Edmund

Dett, R. Nathaniel

Elie, Justin

Ellington, Edward K. "Duke"

Euba, Akin

Garcia, José Mauricio Nunes

Hailstork, Adolphus C.

Holland, Justin

Jeanty, Occide

Johnson, James Price

Joplin, Scott

Kay, Ulysses Simpson

Khumalo, Mzilikazi

Lambert, Charles Lucien, Sr.

Lambert, Lucien-Leon G., Jr.

Lamothe, Ludovic

Leon, Tania

Moerane, Michael Mosoeu

Perkinson, Coleridge-Taylor

Pradel, Alain Pierre

Price, Florence Beatrice Smith

Racine, Julio

Roldan, Amadeo

Saint-Georges, Le Chevalier de

Sancho, Ignatius

Smith, Hale

Smith, Irene Britton

Sowande, Fela

Still, William Grant

Walker, George Theophilus

White, José Silvestre

Williams. Julius Penson

AfriClassical Blog

Companion to AfriClassical.com

Guest Book

William J. Zick, Webmaster,

wzick@ameritech.net

©

Copyright 2006-2022

William J. Zick

All rights reserved for all content of AfriClassical.com

Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, an African

Ignatius Sancho

Vincent Carreta, Editor

Penguin Books (1998)

Microsoft Encarta Africana Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition

|

Home ->

Composers -> Sancho, Ignatius

Français

1 Birth

Ignatius Sancho

(1729-1780) was an African composer and author who grew up as a

house slave in an aristocratic household in Greenwich, England.

He writes in one of his published letters that he was born in

Africa. For over 200 years, the generally accepted version of

his birth and early life was that found in Joseph Jekyll's brief

biography,

Life of

Ignatius Sancho,

published in 1782.

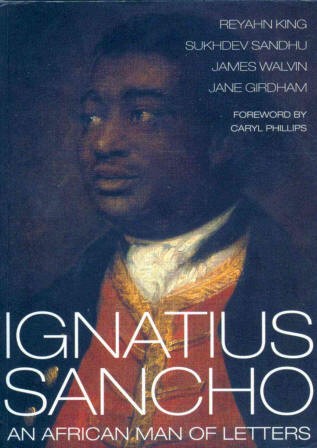

The book pictured above is Ignatius Sancho: An

African Man of Letters. It was written by Reyahn King,

Sukhdev Sandhu, James Walvin and Jane Girdham, and was published

by the National Portrait Gallery of Great Britain (1997).

2 Biography

Joseph

Jekyll

writes that Ignatius Sancho was born on a British slave ship off

the coast of Guinea, West Africa en route to the Spanish West

Indies. He tells us the child's mother died shortly after giving

birth, and his father committed suicide to avoid a life of

plantation slavery. He further says the child was baptized by

the Bishop of Cartagena, in what is now Colombia, was taken to

England, and was given to three sisters who shared a home in

Greenwich. Jekyll gives a detailed account of the youth's

domestic service, his self-education with the assistance of

books provided by a neighbor, the Duke of Montagu, his

emancipation and subsequent employment in the Montagu household.

3 Brycchan Carey

Dr.

Brycchan Carey of London's Kingston University has published "The

extraordinary Negro": Ignatius Sancho, Joseph Jekyll, and the

Problem of Biography',

British Journal for

Eighteenth-Century Studies,

26, 2 (Spring 2003), 1-13. His website on Sancho is

http://www.brycchancarey.com/index.htm It reproduces the

complete text of Joseph Jekyll's

Life of Sancho.

Dr. Carey writes, in part:

|

The major problem with Jekyll's

Life of Ignatius

Sancho

is that much of it is unverifiable, and, worse still,

much of it directly contradicts what Sancho himself says

to people in his letters. For example, although Jekyll

tells us that Sancho was born on a slave ship, Sancho

himself seems convinced that he was born in Africa. For

a more detailed reading of Jekyll's

Life of Ignatius

Sancho,

see my article...that shows that Sancho was almost

certainly not born on a slave ship. |

4 Black

Domestics

Chapter 3 of the Sancho biography is by James Walvin and is

entitled Ignatius

Sancho: The man and his times.

Walvin writes:

|

This

was the period when fashion decreed the use of black

domestics, both enslaved and free. In the homes of

wealthy Londoners, fashionable spas and stately homes,

black pages or servants were commonplace, a fact amply

confirmed in any number of 18th Century portraits.

|

5 Montagu

Family

We do not know exactly how Sancho left the household in which he

was raised, but research has documented his subsequent

connection with the Montagu household. Walvin describes Sancho's

new life:

|

There,

working as a butler, he flourished, reading voraciously,

writing prose, poetry and music. He became an avid

theatre-goer and a fan of Garrick and became a figure in

fashionable London society - friendly with actors,

painters and, most interestingly with Laurence Sterne.

|

6

Marriage

Sancho married Anne Osborne, a West Indian woman of African

descent, in 1758. They eventually had six children. The cover

portrait of the Sancho biography was done by the renowned

British painter Thomas Gainsborough in 1768. Walvin indicates

that Sancho had become a man of letters by that time:

|

By the

late 1760s Sancho had made the progression from being a

decorative black domestic to a man of refinement and

accomplishment, penning letters to friends and

sympathisers around the country. |

7

Shopkeeper

Sancho became chronically ill with gout, and had difficulty

fulfilling his duties as a butler. The Montagu family provided a

small amount of money which enabled Sancho to leave domestic

service and buy a little grocery shop in Westminster, London in

1773. The city had about 20,000 such shops at the time, selling

such staples as sugar, tea and tobacco. Walvin notes the irony

of Sancho's sale of products connected with slavery:

|

As

Sancho tended to his counter and customers - taking tea

with favoured or famous clients - his wife Anne worked

in the background, breaking down the sugar loaves into

the smaller parcels and packets required for everyday

use. Slave-grown sugar, repackaged and sold by black

residents of London, themselves descendants of slaves -

here was a scene rich in the realities and the symbolism

of Britain's slave-based empire. |

8

Voter

Sancho's shop in Westminster was modest in size, yet it received

a steady stream of customers who sought his advice and company

as well as his goods. Walvin relates:

|

Among

the prominent visitors to Sancho's shop was Charles

James Fox, leader of contemporary parliamentary radicals.

We know that Sancho voted for Fox at the 1780 election,

having acquired the right to vote by his property rights

as a shopkeeper in Westminster. From what we know of

Sancho's views, it is not surprising that he voted for

Fox, but it is surely remarkable that at the high

watermark of British slavery a black should cast a vote

in a British election. |

9

Correspondence

Sancho is best known for the numerous letters he exchanged with

a variety of people throughout Britain. A common theme was his

moral outrage at slavery. Walvin elaborates:

|

In the decade

before his death in late 1780, Sancho, now in his

forties, became an inveterate letter-writer. He had made

earlier attempts at writing, but his subsequent

reputation was founded in the letters he penned in the

1770s. |

Among his

most prominent correspondents was Laurence Sterne, the British

author and country pastor who wrote the novel

The Life and Opinions of

Tristram Shandy.

The work was published in nine volumes over a period of ten

years, beginning in 1759. It includes many references to

intellectuals and authors. Sancho first wrote to Sterne in

response to his strong condemnation of slavery in the novel.

10 Letter to Sterne

The sentimental style

of the period is on full display in these excerpts from Sancho's

initial letter to Laurence Sterne. Sancho told the novelist that

he had read of opposition to slavery in the work of only one

author other than Sterne, Sir George Ellison:

|

REVEREND SIR,

IT

would be an insult on your humanity (or perhaps look

like it) to apologize for the liberty I am taking.—I am

one of those people whom the vulgar and illiberal call "Negurs."—The

first part of my life was rather unlucky, as I was

placed in a family who judged ignorance the best and

only security for obedience.—A little reading and

writing I got by unwearied application.—The latter part

of my life has been—thro' God's blessing, truly

fortunate, having spent it in the service of one of the

best families in the kingdom.—My chief pleasure has been

books.—Philanthropy I adore.

...

In your tenth discourse, page seventy-eight, in

the second volume—is this very affecting passage—"Consider

how great a part of our species—in all ages down to this—have

been trod under the feet of cruel and capricious tyrants,

who would neither hear their cries, nor pity their

distresses.—Consider slavery—what it is—how bitter a

draught—and how many millions are made to drink it!"—Of

all my favorite authors, not one has drawn a tear in

favor of my miserable black brethren—excepting yourself,

and the humane author of Sir George Ellison.

—I

think you will forgive me;—I am sure you will applaud me

for beseeching you to give one half-hour's attention to

slavery, as it is at this

day practised in our West Indies.—That subject, handled

in your striking manner, would ease the yoke (perhaps)

of many—but if only of one—Gracious God!—what a feast to

a benevolent heart! |

11 Black

Britons

Sancho vigorously opposed slavery in British colonies, but he

also painted a stark picture of the African community in Britain

itself, a result of the slave trade. In his chapter of

Ignatius Sancho: An African

Man of Letters,

Sukhdev

Sandhu paraphrases Sancho's account of a family excursion by

boat to New Spring Gardens:

|

The London mob

often treated foreigners with contempt. On their way

home from the Gardens, the Sanchos 'were gazed at –

followed, &c. &c. - but not much abused.' |

12

Death

Sancho continued to correspond with his friends during his

long struggle with gout. He finally died in London on December

14, 1780. His letters were published as a book in 1782, with Jekyll's Life of Sancho

used as a

Preface. Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, An African

quickly became a bestseller. We learn from Dr. Brycchan Carey:

|

Sancho's son,

William, added a long footnote to this biography in the

1803 edition. |

13

Slavery Exhibit

Late in 2007, London's Museum in Docklands announced “London,

Sugar & Slavery” a permanent exhibit to commemorate the 200-year

Anniversary of Britain's Abolition Act:

|

On 10 November 2007,

Museum in Docklands will open the only permanent gallery

in London to examine the city’s involvement in

transatlantic slavery and its legacy on the capital.

...

London, Sugar &

Slavery

will show it was not just a few evangelical

parliamentarians who abolished the transatlantic slave

trade, but a widespread grass roots movement that

included people freed from enslavement who wrote about

their experiences, thousands of ordinary citizens who

lobbied collectively and women who campaigned with their

purses by boycotting sugar that had been produced by

enslaved Africans. |

14 African Voices

The

blog Sierra Eye elaborated on this idea on the opening day of

the exhibit, listing Ignatius Sancho among those Africans who

made themselves heard in opposition to slavery:

|

The Buxton table, at

which the terms of the Abolition Act were hammered out,

will be on display. But the gallery will debunk the myth

that abolition was achieved by a few evangelical

parliamentarians. Olaudah Equiano, Ottobah Cugoano,

Ignatius Sancho, Phillis Wheatley and Mary Prince, are

amongst those African voices whose eloquent testimony

were crucial to forcing change. London, Sugar & Slavery

acknowledges enslaved Africans as the prime agents of

resistance. |

15

Black Musicians

Chapter 4 of the Sancho biography was written by Jane Girdham

and is entitled Black Musicians in England: Ignatius Sancho

and His Contemporaries. Girdham mentions some of the other

musicians of African descent who were prominent in Britain

during Sancho's era. They include the British violinist George

Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower (1778-1860) and Joseph Boulogne,

Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745-1799), born on a French

plantation in the Caribbean. Both are featured on their own

pages in this Web site.

16 Legacy

Girdham points out that Sancho was much better known for his

letters than for his musical activities. She quotes Dr.

Josephine Wright's description of Sancho's works which have

survived to today:

|

Ignatius Sancho was one of the few Africans in

18th-century England to become a member of the middle

class, highly literate and an amateur musician and

composer. He was recognised in his lifetime as a man of

cultivated taste in various artistic areas, but his

legacy of four volumes of published music provides

virtually our only information about his musical

activities.

...

Sancho's surviving music consists of one set of songs

and three sets of dances, all published over roughly a

twelve-year period between 1767 and 1779, and totalling

62 short compositions (Wright, 1981, pp. 3-62). |

Because of his

amateur status, Sancho paid the costs of printing his music

himself. Girdham finds his songs to be among Sancho's "most

appealing" pieces. She explains they were written in the

"galant" style which was fashionable at the time. The songs

include settings of poems by Shakespeare, Anacreon and David

Garrick. Garrick was a friend whom Girdham describes as "the

most famous actor of his time" and the owner of the Theatre

Royal Drury Lane. Girdham closes her chapter with this

observation:

|

Although Sancho always remembered that his was an

adopted culture, his musical compositions are some of

the best proof of his assimilation into that culture. |

17 Renaissance Man

The

American scholar Josephine B. Wright edited

Ignatius Sancho (1729-1780),

An Early African Composer in England: The Collected Editions of

His Music in Facsimile, Garland

Publishing, Inc. (1981). A 15-page introduction provides

extensive historical context as well as analysis. Dr.

Wright calls Sancho "a Renaissance man":

|

In

addition to black performers, there were to be found in

Georgian England black composers. One early African

composer who lived in that country was Ignatius Sancho

(1729-1780), a Renaissance man of learning and

apparently the first black musician to publish his

music. This volume is devoted to his biography and a

study of his musical compositions. An investigation of Sancho's music is long overdue in light of the

composer's historical significance as a black

intellectual of the eighteenth century and the increased

public interest in African and Afro-American history.

...

He was conversant with the writings of Voltaire, the

abolitionist literature of Sterne and Sharp, as well as

with the poetry of his contemporary, the Afro-American

slave Phyllis Wheatley (ca. 1753-1784). |

18 Songs

In her Introduction to

Sancho's music, Josephine Wright critiques the volume entitled

A Collection of New Songs:

|

Of the

published volumes, A Collection of New Songs

is perhaps Sancho's

most interesting. These songs were published

originally for soprano voice with keyboard accompaniment.

But the compositions are decidely suitable for any voice

type, and may be easily transposed into various keys for

this purpose.

In general, Sancho

adheres to simple binary-strophic forms with contrasting

A and B sections.

Only

one song, "Take, Oh Take Those Lips Away," is

through-composed. The average length of the songs

is from twenty-four to forty-two measures. |

19 Significance

Though Ignatius Sancho was

only a skilled amateur composer, Josephine Wright stresses the

historical significance of his music:

|

There

can be no pretense that the music of Ignatius Sancho

equals that of the leading composers of his day.

But his musical compositions reveal the hand of a

knowledgeable, capable amateur who wrote in miniature

forms in an early Classic style. His compositions

are of great historical significance in understanding

the roots and origins of a classical tradition among

black musicians in the Western hemisphere. His

published music records the achievements of one black

composer from the eighteenth century who was active at a

time when most persons of African descent were chained

by the bonds of slavery on both sides of the Atlantic. |

This page was last updated

on

March 5, 2022

|