Home

Blog

Composers

Musicians

Black History

Audio

About Us

Links

Composers:

Adams, H. Leslie

Akpabot, Samuel Ekpe

Alberga, Eleanor

Bonds, Margaret Allison

Brouwer, Leo

Burleigh, Henry Thacker

Coleridge-Taylor, Samuel

Cunningham, Arthur

Dawson, William Levi

Dede, Edmund

Dett, R. Nathaniel

Elie, Justin

Ellington, Edward K. "Duke"

Euba, Akin

Garcia, José Mauricio Nunes

Hailstork, Adolphus C.

Holland, Justin

Jeanty, Occide

Johnson, James Price

Joplin, Scott

Kay, Ulysses Simpson

Khumalo, Mzilikazi

Lambert, Charles Lucien, Sr.

Lambert, Lucien-Leon G., Jr.

Lamothe, Ludovic

Leon, Tania

Moerane, Michael Mosoeu

Perkinson, Coleridge-Taylor

Pradel, Alain Pierre

Price, Florence Beatrice Smith

Racine, Julio

Roldan, Amadeo

Saint-Georges, Le Chevalier de

Sancho, Ignatius

Smith, Hale

Smith, Irene Britton

Sowande, Fela

Still, William Grant

Walker, George Theophilus

White, José Silvestre

Williams. Julius Penson

Guest Book

William J. Zick, Webmaster,

wzick@ameritech.net

©

Copyright 2006 - 2022

William J. Zick

All rights reserved for all content of AfriClassical.com

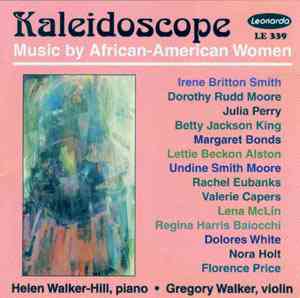

Kaleidoscope: Music by African-

American Women; Helen Walker-Hill, piano; Gregory Walker,

violin; Leonarda 339 (1995)

|

Home ->

Composers -> Smith, Irene Britton

Français

1 Helen Walker-Hill

The principal source for this

essay on Irene Britton Smith is the book

From

Spirituals to Symphonies: African-American Women Composers and

Their Music, written by

Helen Walker-Hill and published by the University of Illinois Press

(2007). Dr. Walker-Hill is a former member of the Piano faculty

at the University of Colorado Boulder. She begins by

explaining her purpose in interviewing Irene Britton Smith:

|

Because

she was reported to have known the composers Florence

Price and Margaret Bonds, I contacted Irene Smith in the

summer of 1989 and asked for an interview. She

replied that, yes, she had known Margaret Bonds and

Florence Price, and she would be willing to talk about

them. |

Two

other reference sources by Dr. Helen Walker-Hill are:

Women of Note Quarterly, Chicago Composer Irene Britton Smith;

FEB 97: Vol 5:1:5-8 and the Irene

Britton Smith entry in the

International Dictionary of Black Composers,

edited by Dr. Samuel A. Floyd, Jr. and published in 2 volumes by

the Center for Black Music Research at Columbia College Chicago

(1999).

2 Discovery

Dr. Walker-Hill describes the indirect manner in which she learned

that Irene had done her own composing:

|

Only in

passing did it emerge that she herself composed.

As she brought out her meticulously copied compositions,

it became evident that hers was a highly trained and

sensitive talent. She had learned her craft in

relative obscurity during years of dedicated study with

some of the leading musicians and teachers of the

twentieth century. Although music and composing

may have been the love of her life, most of her energy

was required in her profession of teaching in the public

schools. |

|

3 Birth

Irene Britton Smith was born in Chicago on December 22,

1907, the biography tells us, and grew up on the South side of

the city. She lived in an apartment in the area for 42

years. Walker-Hill provides details of her early education:

|

She attended

Ferron Grammar School, then completed the seventh and

eighth grades at Doolittle Grammar School, two blocks

away. For her secondary education she went to

Wendell Phillips High School. |

4 Father

From Spirituals to Symphonies relates that Smith's father

grew up on a farm near Maysville, Kentucky and attended

Louisville College before relocating to Chicago. The book

reports that the composer's father had both Native American and

African American heritage:

|

He was of Crow

and Cherokee as well as African-American descent; his

Crow grandmother lived with his family until she died at

age 93. This ancestry is evident in photographs

from his straight hair and prominent cheekbones.

Irene recalled that as a child she liked to stand behind

his chair and comb his hair. In Chicago he held a

position as a clerk in a manufacturing company.

Irene could remember that during the race riots of the

"Red Summer" of 1919, his company sent an escort to

protect him on the way to and from work. |

5 Mother

Helen Walker-Hill writes that Smith's mother was from Detroit

and played the piano by ear:

|

Her mother, who came

to Chicago from Detroit, was musical and loved to play

hymns by ear, "favoring the black keys." She had

acquired a piano before Irene was born, and as a small

child, Irene began composing little pieces on it. |

6

Childhood

Irene had two brothers who died while still infants, Walker-Hill

tells us, and an older sister who passed away in the 1980s. She continues:

|

When Irene was

10, her parents separated and she was sent to a Catholic

boarding school for a year. Later she and her

sister took piano lessons from V. Emanuel Johnson, who

made them play duets. "He was the kind who hits

you on the fingers." |

7

Violin Lessons

The author

writes that Smith developed an interest in the violin while in

her high school orchestra:

|

When Irene

accompanied her high school orchestra, she became

fascinated with the violin section and started to teach

herself on her sister's violin. She was then given

lessons, and attended her first symphony orchestra

concert at Orchestra Hall as a guest of her public

school violin teacher when she was 14 years old. |

8

Teaching

We learn

from Walker-Hill that Irene desired to study Music in college,

but was thwarted by financial reality:

|

Irene had ambitions to study music at Northwestern

University but her parents couldn't afford it, so she

turned instead to the two-year course at Chicago Normal

School to prepare herself to teach in the elementary

grades. |

9 Music

Studies

Although

Irene accepted teaching as her means of supporting herself, she

promptly began pursuing her avocation of Music on a part-time

basis, the book relates:

|

After

being assigned to teach primary grades in the Chicago

public schools, she decided to take a course in music

theory, which she had longed to study for many years.

She took one course a year at the American Conservatory,

beginning with theory and harmony for two years, then

progressing through form and analysis, and counterpoint. |

10 Berean Baptist Church

Margaret

Allison Bonds, who is also profiled at AfriClassical.com, was

one of many Black musicians who frequented the Berean Baptist

Church, according to the biography:

|

During the

1930s, Irene attended the Berean Baptist Church along

with a good number of other musicians who were

well-known in the black community. These included

Estella Bonds, church organist, and her daughter,

Margaret. Smith knew the Bonds family well, and

was good friends with Estella's sister Helen. |

11

Violinist

Walker-Hill tells of Irene's role as violinist in a Black

symphony orchestra and in the student orchestra at the American

Conservatory:

|

Irene played

violin in the all-black Harrison Ferrell Symphony

Orchestra, which rehearsed at the church and gave yearly

concerts at Kimball Hall. She was later a member

of the student orchestra at the American Conservatory. |

12

Marriage

Irene married in 1931, the year she turned 24, we learn from the

biography. Her husband's educational and career

aspirations were complicated by the lack of equal employment

opportunity for people of color, so a lengthy separation ensued:

|

In 1931 Irene

married Herbert E. Smith, an employee of the postal

service. Smith had greater ambitions, and returned

to school for a master's degree in chemistry at Bradley

University in Peoria. But after he finished his

degree, he found that it was still very difficult for

qualified blacks to get jobs in Illinois. For a

period of 10 years during the 1940s and 1950s, Irene and

her husband lived apart while they both pursued their

degrees. |

13

Reunited

Irene and

Herbert reunited, Helen Walker-Hill writes, and lived together

until his death:

|

She recalled

that he would send her a dozen roses on their

anniversary, even during their years of separation.

They later reunited, and he eventualy worked for the

U.S. Department of Agriculture on such projects as the

development of gasohol. The couple remained

childless, and in December 1975 her husband passed away.

|

14

Florence B. Price

From Spirituals to Symphonies makes it clear that

personal correspondence of the composer is included in the

"Irene Britton Smith Collection" at the Center for Black Music

Research, Columbia College Chicago:

|

In 1936

Smith wrote to Florence Price, already well-known as a

composer, after hearing her give a talk. Price

responded with a letter saying, "It was very kind of you

to say you enjoyed my little talk at Lincoln Center, and

it makes me happy indeed to know that you received

encouragement from it. That you find the study of

composition such a pleasure indicates that we may expect

to hear from you some of these days. I should be

very glad to see some of your work if you care to call a

few days ahead of time and make an appointment." |

15

Theory & Composition

The author concludes that Irene's personality kept her from

accepting Florence Price's invitation:

|

Smith was

too shy to accept Price's invitation. But Price's

words encouraged her, and she decided to work toward a

degree in theory and composition at the American

Conservatory, with the approval of her instructor,

Stella Roberts, and Dean Charles Haake. She

continued to take one music course each year, including

violin and voice (she was also proficient in piano and

organ), and in her last two years she studied

composition with Leo Sowerby. She distinguished

herself in these studies, receiving an Honorable Mention

in theory and analysis at the 1938 commencement

exercises of the American Conservatory of Music. |

16 B.A.

in Music

We learn from Dr. Walker-Hill that Irene composed an increasing

number of works in the later years of her studies at the

American Conservatory:

|

Smith's

composition gathered momentum in 1940-41, the years in

which she wrote several ambitious works: Passacaglia

and Fugue in C-sharp Minor, and Invention in Two

Voices for piano, Psalm 46 for chorus and

baritone, and Reminiscence for violin and piano,

which was performed in May of the following year by

violinist Adele Mdjeska. In 1943, after 11 years

of study, she completed her bachelor's degree in

composition at the American Conservatory. |

|

17

Juilliard

In 1946 Irene Britton Smith successfully submitted a hymn for

publication, the biography tells us, and she undertook graduate

studies:

|

Further

impetus came in 1946 when Fairest Lord Jesus, her

choral work for women's voices and organ on the words

from the Crusader's Hymn, was accepted for publication

by the prestigious New York publishing firm G. Schirmer.

That year she was on sabbatical leave from the Chicago

public school system and went to New York for graduate

study at the Juilliard School of Music. |

18

Vittorio Giannini

Both of Smith's courses at Juilliard were taught by Vittorio

Giannini, we learn from From Spirituals to Symphonies:

|

She chose two

courses taught by Vittorio Giannini, one in song forms

and the other in larger forms of composition. Smith

recalled that when she brought her setting of the Paul

Laurence Dunbar text "Why Fades a Dream?" to Giannini,

he exclaimed, " 'Who is this poet?' He went out

and bought a whole book of Dunbar poetry. He liked

it [the song] and he's the one who suggested to me that

I write a cycle." For her class in larger forms,

Smith completed her Sonata for Violin and Piano. |

19

Summer Studies

The author writes that Smith subsequently continued music

studies in Chicago, and devoted many of her Summer vacations to

graduate study as well:

|

Upon returning

to Chicago and her classroom teaching, Smith resumed

studies in composition with Leon Stein at De Paul

University. She spent several summer vacations

away from Chicago, studying with well-known composers

and teachers. In the summer of 1948, she studied

contemporary harmony at the Eastman School of Music with

Wayne Barlow. In 1949 she was at Berkshire Music

Festival in Tanglewood, working with Hugh Ross in choral

conducting and studying composition with Irving Fine.

...

She met Julia Perry and showed her some of her

compositions. "In addition to Julia Perry, Elayne

Jones, Mattiwilda Dobbs, and I were the only black women

attending." |

20

Nadia Boulanger

Smith completed her Master's Degree at De Paul University in

1956, Dr. Walker-Hill relates, and in 1958 studied in France

with Nadia Boulanger:

|

Smith

completed her master's degree in theory and composition

at De Paul University in 1956. In the summer of

1958 she fulfilled a dream to study with the famed

teacher Nadia Boulanger at the American Conservatory at

Fontainebleu, France. Boulanger praised her

compositions and told her, "You are a born musician.

Follow your ear." |

21

Reading Method

Irene Britton Smith taught Reading in the Chicago Public Schools

for more than 40 years, the author writes, and last taught at

Pershing Elementary School, from 1958 to the year of her

retirement, 1978. Dr. Walker-Hill continues:

|

She adopted

the phono-visual mehod of teaching reading after

attending a demonstration at Northwestern University in

1957. It was remarkably successful, enabling her

students to consistently leave first grade with third,

fourth and even higher grade levels. For the next

decade, her energies went into giving workshops, and

promoting and using this teaching technique. |

22

Docent

The

biography relates that Irene organized rhythm bands for school

children, and that annual performances were given at the

Cosmopolitan Community Church. The author continues:

|

Smith's

concern for young people was also evident in her

volunteer work as a docent for the Chicago Symphony

Orchestra in the Chicago public schools, which she began

soon after her retirement from classroom teaching in

1978. |

23

Performances

Irene's music began to be performed more recently in the 1970s,

the author relates. She continues:

|

Her spiritual

arrangement for baritone and piano, Let Us Break

Bread Together,was sung in 1972 by Theodore Charles

Stone, noted concert artist and music critic for the

Chicago Defender. In 1984 it was performed

again, at the Second Presbyterian Church, where her

Fairest Lord Jesus was later programmed (1989).

Songs from her Paul Laurence Dunbar Dream Cycle

were performed by several noted artists and broadcast

over WFMT, drawing a congratulatory letter from Cyrus

Colter, chairman of the African-American studies

department at Northwestern University. |

24

Continued Learning

From

Spirituals to Symphonies indicates that Smith continued to

learn about Music, even after she stopped composing:

|

In later

years, her only outside activity was attending the

Chicago Symphony Orchestra music appreciation classes

and concerts. She never stopped expanding her

knowledge of music. In the mid-1970s she wrote to

Stella Roberts, "I haven't written any music for 15

years. However, I do not regret one minute of

learning about music and composition, and I still

continue to learn. I read current periodicals and

books on music." |

25

Kaleidoscope

One of

Irene's works, her Sonata for Violin and Piano (15:07)

was published by Vivace Press in 1996 and is included on the CD Kaleidoscope: Music by

African-American Women; Leonarda LE 339 (1995). The

performers are Helen Walker-Hill, piano, and Gregory Walker,

violin. Notes, the Quarterly Journal of the Music

Library Association called the CD:

|

...good

music that has been overlooked and underrepresented in

the traditional repertory... |

26 Death

From Spirituals to Symphonies

has this to say about the compact disc and the

composer's death:

|

For the last

few years of her life, Smith lived in the Montgomery

Place Retirement Home on Chicago's South Shore Drive.

During this time her Sonata for Violin and Piano

was published and issued on a CD recording, but she had

difficulty recognizing her own music because she

suffered from Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's

disease. On 15 February 1999, at the age of 91,

she died of complications from these diseases.

Services were at the Griffin Funeral Home, and she was

buried in Lincoln Cemetery, where Florence Price is also

buried. |

27 Papers

Irene Britton Smith's papers were donated to the Center for

Black Music Research at Columbia College Chicago,

where they now constitute the "Irene Britton Smith Collection."

Dr. Walker-Hill writes:

|

In accord with

her wishes, her papers and music scores were given to

the Center for Black Music Research (CBMR) at Columbia

College Chicago. |

28 Racial Identity

Helen Walker-Hill comments on the composer's racial

identity:

|

Smith's

attitude toward race seemed ambivalent, and her remarks

were often contradictory.

...

Smith's compositional style displayed no trace of black

idioms. She didn't think that her experiences as a

black person had any bearing on her composition, yet her

use of poems by Paul Laurence Dunbar and her

arrangements of spirituals indicate her sense of racial

identity. She had no objection to being

categorized as a black woman composer for this study,

and said, "I think that's good. That's the only

way we're going to get known."

It was in her poetry that Smith revealed her loyalty to

and identification with her race. Two of her poems

in the archives at CBMR celebrate the strengths of

African Americans and her sense of belonging to "my

people." |

29

Compositions

About three dozen of Smith's works are now known to have

survived. Dr. Walker-Hill's 1997 article in Women of

Note Quarterly, Chicago Composer Irene Britton Smith, was

published while Smith was still alive:

|

The

compositions she is willing to show number only about

fifteen, and do not include the "sonatinas, inventions,

and suites" of her early years. All together,

according to her estimate, she has composed about 30

works.

...

A set of four songs, Dream Cycle (1946-47), on

poems by Dunbar has been performed, notably by soprano

Jo Ann Pickens at the Chicago Public Library's Myra Hess

Concerts in 1977 and in New York at the Harlem School of

the Arts in a concert broadcast on WQXR Radio. Her

arrangement of the spiritual "Let Us Break Bread

Together" (1948) has been sung by a number of Chicago

musicians. |

30 Vocal & Instrumental

The

biography identifies the number of Smith"s works

in each of several categories:

|

Seventeen of

the total of 36 compositions, a little less than half,

are purely instrumental works, and 19 are vocal.

Of the vocal works, seven are choral, while 12 are for

solo voice or voices. Ten instrumental works are

for solo piano (including two arrangements of Bartok),

two are for violin (surprisingly little, since she was a

violinist) one is for string trio, and four are for

orchestra (including an arrangement of Three

Fantastic Dances by Shostakovich). Spiritual

arrangements account for six of the vocal pieces. |

31 Sheet Music & Recordings

From

Spirituals to Symphonies lists those works of Irene Britton

Smith which have been published and recorded:

|

Smith had one

choral anthem published by G. Schirmer (1946), the

Crusader Hymn Fairest Lord Jesus for women's

voices, but it is now out of print and the copyright was

returned to her. Vivace Press published her

Sonata for Violin and Piano in 1996 and four of her

solo piano works in 2001. The Sonata for Violin

and Piano is the only work available on recording (see

discography). |

32 Sinfonietta

In Women of

Note Dr.

Walker-Hill analyzes the choral and vocal works, and refers to

other short pieces by Smith:

|

These

choral and vocal works display Smith's elegant

simplicity, her exquisitely placed harmonic color,

discreetly cultivated contrapuntal commentary, and

over-all formal balance.

There are other choral anthems and songs, a

Sinfonietta in three movements for full orchestra,

chamber works, and works for solo piano including two

short Preludes, a Passacaglia and Fugue in c#

minor, and a set of Variations on a Theme

of MacDowell. |

33 Favorite Composers

In her book, the author discusses Smith's harmonic style as well

as some of the principal composers she liked:

|

In harmonic

style, Smith's oeuvre varies from conservative and tonal

to sharply dissonant. Smith's

favorite composers were Tchaikovsky and Brahms, and she

was also fond of the French composers Gabriel Fauré and

César Franck. It was in the music of Franck that

she first discovered augmented sixth chords: "When I

found what an augmented sixth chord would do - I

marvelled!" |

34 International Modernist

From

Spirituals to Symphonies distinguishes Smith from Black

composers whose works use African American idioms or display

"racial" characteristics. Instead the author groups her

among composers whose music reflects "international modernist

attitudes":

|

Smith's music

does not employ African-American idioms or espouse the

"racial" loyalties and characteristics typical of the

music of William Grant Still, Florence Price, William

Dawson, and other black composers of the 1920s and

1930s. She knew the music of Margaret Bonds and

admired her craft,but she did not share her social

concerns or her enthusiasm for popular traditions.

Her attitude was closer to the international modernist

sensibility of the 1950s and 1960s, which governed the

work of Julia Perry, George Walker, Hale Smith, and

other black composers. |

35 Composed Linearly

The book

quotes Irene Britton Smith as saying she composed "linearly."

|

Smith's

process of composition usually began with a melodic idea.

Then a countermelody would immediately suggest itself.

She said, "I think and compose linearly," that is, in

horizontal melodic lines rather than vertical harmonies.

She preferred to compose away from the piano, and was

aided in this by perfect pitch. She did not need

to play her music or hear it played, because she could

hear the entire work in her head. |

36 Mastery of Composition

Dr.

Walker-Hill discusses the positive attributes of Smith's works

at length in the book, and quotes the composer on the reason for

her mastery of composition:

|

Smith's works

display an elegant simplicity, overall formal balance,

discreetly placed harmonic color, subtle contrapuntal

details, wide pitch range, and open textures. She

attributed her mastery of composition to her excellent

training, as she commented in a letter to her former

teacher Stella Roberts: "I can listen to music and

evaluate it mentally whether it be traditional,

contemporary or avant-garde, and all of this I can do

because of the thoroughness of the theory I received

from you at the American Conservatory..." |

37 CD Reviews

Smith's

Sonata for Violin and Piano (15:07) is the longest work on

the CD Kaleidoscope: Music by African American Women

Leonarda LE

339 (1995, and it drew a number of comments from reviewers, as

Helen Walker-Hill relates in her book:

|

The reviewer

for the American Record Guide complained that it

was "incessantly melodic but dull and tensionless," but

Strings magazine gave it a glowing review as "an

outgoing and elegantly designed work in the American

neoclassical tradition, and deserves further listening."

Other reviewers also were favorably impressed.

Barbara Harbach pronounced it "an exciting contribution

to the violin and piano literature, rewarding not only

to its performers, but also its listeners," and found it

"immediately appealing...[with] long expressive lyrical

melodies, careful and intriguing placement of unexpected

harmonies, playful and imaginative interaction between

the violin and the piano, touches of chromaticism, and

alternating moods and tempos." Rae Linda Brown

considered it a "highlight of the CD...a substantial (almost

fifteen minutes) work in the late nineteenth-century

romantic tradition. Tonally conservative, it is

not without technical demands. The work requires

complete balance between the two instruments." |

38 Archives

In addition

to the Irene Britton Smith Collection at the Center for Black

Music Research, Columbia College Chicago, From Spirituals to

Symphonies lists as a resource on the composer:

|

The Helen

Walker-Hill Collection, located in duplicate at the

American Music Research Center at the University of

Colorado and at the Center for Black Music Research,

Columbia College Chicago. |

39 Legacy

The legacy of Irene

Britton Smith is manifest in the lives and careers of her

students. Patricia Pates Eaton is a living example of

Smith's mentoring, which she recalls:

|

I have just

retired from teaching music in the NYC Public School

System, however I continue to be the Principal Conductor

of the All City High School Chorus and I conduct a

community choir, The Brooklyn Ecumenical Choir of

Bedford Stuyvesant.

...

Irene B. Smith was my first grade teacher at Forestville

School who recommended my first piano teacher, Muriel

Rose, to my parents when I was 6 years old. She took me

to rhythm band rehearsals at her church, Cosmopolitan

Community Church, on Saturday mornings when I was 6

years old. She attended my piano recitals and orchestra

concerts when I became a member of the All Chicago Youth

Orchestra.

...

There is no time that I am asked how and why I

became a musician that I don't mention her name because

I stand firmly on her shoulders. |

Patricia Pates Eaton

has been a professional chorister in Metropolitan Opera

productions in New York City, including Aida and Boris

Gudanov; has worked with the Alvin Ailey Dance Theatre and

New York Philharmonic, among many other groups; has given

recitals as a soprano soloist; and has performed several roles

in operas, including Civil Wars by Phillip Glass and 'X'

the Life And Times of Malcolm X by Anthony Davis.

This page was last updated

on

March 5, 2022

|