Home

Blog

Composers

Musicians

Black History

Audio

About Us

Links

Musicians:

Blanke, John

Bridgetower, George A. P.

Chapman Nyaho, William H.

DePreist, James

Dworkin, Aaron Paul

Freeman, Paul

Johnson, Francis

Machado, Celso

Ngwenyama, Nokuthula

Wiggins, Thomas "Blind Tom"

Yifrashewa, Girma

AfriClassical Blog

Companion to AfriClassical.com

Guest Book

William J. Zick, Webmaster,

wzick@ameritech.net

©

Copyright 2006-2022

William J. Zick

All rights reserved for all content of AfriClassical.com

Blind Tom,

The Black Pianist-Composer: Continually Enslaved

Geneva Handy Southall

Scarecrow Press (2002)

FI-YER!, A

Century of African American Song

That Welcome Day

Thomas Greene Bethune, aka

Thomas "Blind Tom" Wiggins

William Brown, tenor

Ann Sears, piano

Troy 329 (1999)

An Anthropologist On Mars:

Seven Paradoxical Tales

Oliver Sacks

Vintage Books USA (1996) |

Home ->

Musicians -> Wiggins, Thomas "Blind

Tom"

Français

Thomas "Blind Tom"

Wiggins (1849-1908)

African American Pianist and Composer

A Blind And Autistic Slave Was A Musical Genius

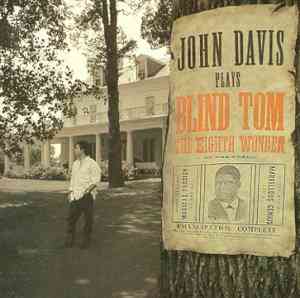

Audio Sample:

John Davis Plays Blind Tom;

John Davis, Piano; Newport Classic

85660 (1999) The Rainstorm

1 Birth

Thomas Greene Wiggins was born on the Wiley Edward Jones

plantation in Harris County, Georgia on May 25, 1849. He came into the

world blind and autistic but a musical genius with a phenomenal memory.

Even after Emancipation, his former owners kept him, in the words of the

late author Geneva Handy Southall, "Continually Enslaved". His many

concerts and the sale of his sheet music earned fabulous sums of money. Nearly all of it went to his owners and their heirs. Southall's book is

her third volume on Thomas Wiggins. It is based on a quarter century of

vigorous academic research into all aspects of his life and career, and is

the primary source for this Web page.

2 Slave Auction

Professor Southall recounts that young Tom "was 'thrown in' as a bargain"

when his parents and two brothers were sold at a slave auction in 1850:

|

Blind from birth, he was "thrown in" as a bargain when

Colonel James Neil Bethune, a highly respected Columbus,

Georgia lawyer, and newspaper editor purchased his

parents, Charity and Mingo Wiggins, and two of his

brothers at a slave auction in fall 1850. From infancy Tom

manifested an extraordinary fondness for the musical

sounds he heard in the Big House and had shown

exceptional retentive skills. According to most accounts,

Tom demonstrated his aptitude for music before his fourth

birthday, having slipped unnoticed to the piano and picked

out several tunes he had heard played by the Bethune

daughters, all of whom were accomplished musicians. |

3 First Compositions

Southall writes that the entire Bethune family treated Tom as a sort of

"household pet", teaching him to match objects to their names, but his

first music teacher was one of the daughters, Mary Bethune:

|

Mary Bethune became his piano teacher. Because she had

studied with Professor George W. Chase, the highly

respected New York-trained pianist- composer-conductor,

one can assume that Tom received a solid theoretical and

technical musical foundation.

Soon after, his love of music and music-making led him to

write original songs and imitate sounds of nature and other

musical instruments on the piano.

|

Before he was six years old, Tom was being shown off to the Bethune

family's neighbors.

4 Concert at Age 8

Southall describes the response to Tom's first public concert, at age 8,

in Columbus, Georgia:

|

Following his first public concert at Columbus' Temperance

Hall on October 7, 1857, Tom was taken to Atlanta, Macon,

and Athens, where the editor of Athens Southern Watchman described his performance at the University of

Georgia as the "most remarkable ever witnessed in Athens,

one that would put to blush many a professor of music." |

5 Hired Out

The wife of James Bethune died of "pulmonary disease", according to an

obituary in the Columbus Daily Sun on May 22, 1858. Mary Bethune began

looking after her younger siblings. Southall recounts:

|

Shortly thereafter, Tom became a hired-out slave musician

to Perry Oliver,

a Savannah tobacco planter,

under a three-year contractual agreement with Colonel

Bethune, who was

paid $15,000 for the right to exhibit Tom

in other parts of the

country. After several concerts in Savannah, Perry

Oliver

began to exhibit Tom in other

Southern and pro-slavery

states as the "Musical Prodigy of

the Age: a Plantation Negro Boy." |

Southall continues that by 1861 Tom was giving prestigious performances

such as one in Washington, D.C. for the first Japanese diplomats to visit

the United States. As another example of his growing fame, she points out:

|

In addition, his Baltimore concerts of July 1860 had so

impressed the famous piano manufacturer, William Knabe,

that he gave the ten-year-old slave an elaborately carved

rosewood grand piano with a silver plate bearing the

inscription "a tribute to Genius." He was also a published

composer by this time, his Oliver Galop and Virginia Polka

having been published by the prestigious Oliver Ditson

publishing firm in

1860. |

6 Confederate Aid

At the start of the Civil War, Oliver Perry quickly brought Tom back to

Georgia. Ironically, Tom's performances began to benefit the Confederacy.

Southall writes:

|

By October 1862 Tom was back with the Bethunes who

continued to use his talents for the pro-slavery cause. Since the May 10, 1864, Columbus Daily Sun announced

that Blind Tom had "given $5,000 from his recently

completed three month tour to benevolent causes," it is

evident that Tom's concert schedule was both profitable

and exhaustive. Among the works performed on those

programs was his own programmatic piece, titled Battle of Manassas,

written after he heard one of Colonel Bethune's

sons (then a member of the Second Georgia Regiment)

describe that famous Confederate victory. Inasmuch as a

report in the December 17, 1861, Atlanta Southern

Confederacy noted Tom's playing of Dixie with one hand,

Yankee Doodle with the other while singing The Girl I Left Behind Me at the same time, it is apparent that Tom had

been exposed to music and discussions connected with the

Civil War from its outset. |

7 Indenture Contract

James Bethune protected himself against the possiblity of a Union victory

in the Civil War by convincing Mingo and Charity Wiggins to sign an

indenture agreement for Tom's services, on May 30, 1864, for a period of

five years. Bethune promised to provide Tom's parents with "a good home

and subsistence and $500 a year". The 16-year-old performer himself was

assured "$20 per month and two percent of the net proceeds of his

services". The first legal challenge to the indenture was filed in July,

1865 by a Black business man named Tabbs Gross, during an engagement Tom

had in Indiana, claiming that he had a bill-of-sale for Tom's services. James Bethune and his two sons quickly left the state with Wiggins, but

Gross followed them to Cincinnati and filed a Writ of Habeus Corpus

against them. Professor Southall continues the story:

|

As was revealed in my first book of the Blind Tom series

(Minneapolis: Challenge Productions, Inc., 1979), this

historic "guardianship trial," which was held before Judge

Woodruff of the Hamilton County Probate Court, had both

political and racial overtones, and ended with the judge's

decision to allow Bethune, an ex-slave owner, to keep Tom

in a "neo-chattel" relationship. Inasmuch as the

guardianship agreement permitted the Bethunes to

receive ninety percent of Tom's earnings with nothing to

guarantee that they would not expropriate the ten percent

promised to Tom and his parents, the trial offered one more

example of how ex-slave owners were able to re-enslave

their slaves, the Emancipation Proclamation notwithstanding.

In the July 25th, 1865, Cincinnati Enquirer, the editor,

speaking to the humane aspects of the decision, asked:

"why is Tom compelled to support Bethune and his two

able-bodied sons who, fresh from the ranks of treason, are

making the tour of the North with abundant leisure and

purses well filled by the talents of what they would have us

believe, an idiot? Why don't they go to work? |

8 Repertory at Age 16

The biographer gives a detailed account of the classical music repertory

Tom had mastered by age 16, and of his many phenomenal skills as a singer,

pianist and orator:

|

Though Tom was only sixteen at the time of the trial, his

repertory included many of the most technically and

musically demanding works of Bach, Chopin, Liszt,

Beethoven, Thalberg, and other European masters. (See

p. 43). Like other pianists of that time, he demonstrated his

improvisational and theoretical skills by performing

variations and fantasies on operatic airs and popular

ballads of the day. Other astonishing feats included hisalleged ability to perform difficult selections almost

flawlessly after one hearing, sing and recite poetry and

prose in several languages, duplicate phonetically lengthy

orations by noted statesmen, and reproduce sounds of

nature, machines, and musical instruments on the piano.

Being possessed of a rich baritone voice, Tom also

included original and sentimental songs by such English

songwriters as Henry Russell and Henry Bishop in his

concerts. |

9 Music Tutor

The biographer reports that as the legal proceedings dragged on, attorneys

for both parties agreed that Tom could continue to travel and make concert

appearances in the interim. The notoriety generated by the trial helped

draw audiences to Tom's concerts in various cities in Ohio. Promotional

material regularly claimed that Tom was untaught; in fact he traveled with

a high-paid tutor who was a Professor of Music:

|

Despite the fact that Professor W. P. Howard, an Atlanta

music teacher, was accompanying the Bethunes as Tom's

music tutor for what was then an exorbitant salary of $200

a month plus travel expenses, Tom was still being

promoted as a "natural untaught" pianist. Obviously the

Bethunes had decided to retain the characterization of Tom

as an "idiot" whose "incomprehensible creative and

retentive powers" were the result of some "unexplained

satanic gifts" as a promotional gimmick. |

10 Philadelphia

Professor Southall writes that the city of Philadelphia presented special

challenges for Tom's managers. At the end of the Civil War, Philadelphia

had a Musical Fund Society and an Academy of Music. Each had a large

concert hall, regular programs of opera and classical music, and a

sophisticated audience. The author continues:

|

Added to these aspects, Tom was being presented in a city

that was then regarded as the cultural and intellectual

capital of Black America, the city where several Black

musicians had already achieved international acclaim. It

was, after all, Frank Johnson, a Black Philadelphian, who

had in December 1838, introduced thousands of

Philadelphians to the

Parisian-style Promenade Concerts.

These concerts, which were advertised as "Musical

Soirees," took place after Frank Johnson had returned with

his famous all-Black band and orchestra from a successful

tour in England, followed by an extended concert tour in

several northern and eastern cities in the United States. |

After first failing to attract professional musicians to hear him at the

Concert Hall, the Bethunes scheduled an invitational concert for prominent

Philadelphia musicians and scientists. That event won a signed endorsement

from those in attendance, attracting such large audiences to subsequent

performances in the city that Tom's engagement was increased from one week

to four.

11 European Tour

The Bethunes used a subsequent European tour to obtain testimonials from

prominent classical composers. Southall recounts:

|

After a second four-week concert engagement at New

York's Irving Hall (April, 1866), Tom was taken to Europe

where he was continuously subjected to rigorous tests by

noted musicians like Ignaz Moscheles and Charles Halle -

whose testimonial letters were published by the Bethunes

in a pamphlet, The Marvelous Musical Prodigy Blind Tom. |

12 $50,000 Per Year

By 1868 the Bethunes were living on a Warrenton, Virginia farm they called

Elway. Wiggins spent his Summers there, between concert tours around the

U.S. and in Canada, with John G. Bethune serving as his manager. Professor Southall continues:

|

On July 25, 1870, John Bethune had himself appointed Tom's legal guardian in a Virginia Probate Court, thereby negating the 1865 Indentureship Agreement. By now the

Bethunes were realizing $50,000 yearly from Tom's

concerts.

For nine years, Tom lived in New York, since his manager

had married a Mrs. Eliza Stutzback, owner of the

boardinghouse where they stayed. In the summers Tom

studied with Professor Joseph Poznanski, who also wrote

down many of Tom's compositions. When John G.

Bethune was killed (February 16, 1884) trying to board a

train, General Bethune had himself legally appointed

Tom's guardian and continued the concert tours. |

13 Mother

Sues

Southall explains that John G. Bethune's marriage ended before his death,

leading to a legal contest for control of Wiggins and for the money

generated by Tom's performances since 1865:

|

A three year court battle between him and Eliza Bethune,

(who had divorced John Bethune before the accident) for

Tom ended July 31, 1887, when the court granted custody

to the widow. The custody battle began on July 9, 1885,

when Tom's mother, Charity Wiggins, filed a petition in theUnited States Circuit Court, Alexandria, Virginia, for the

return of her son.

Charity Wiggins did not deny that she and Tom's father (the

late Mingo Wiggins) had agreed "with Bethune that he

should have Tom for five years, at the end of which he

would attain his majority." Her concern was that "without

their consent and without giving them notice they had Tom

adjudged to be a lunatic, with the General's son appointed

as the committe of his person, then put him on exhibition

as a pianist." Her suit was therefore against General

Bethune for the "services of her son and an accounting of

the profits of the exhibitions since 1865." |

14 Change of Custody

Professor Southall writes that James N. Bethune finally lost custody of

Thomas Wiggins to Eliza Bethune, as requested by Charity Wiggins:

|

On July 31, 1887, the New York Times reported that Judge

Bond passed an order the previous day in Baltimore which

"took Blind Tom out of General Bethune's custody." It was

reported that:

"James N. Bethune, who has kept Blind Tom in his

possession since the days

of slavery, should deliver him to the United States marshal on August 16 at Alexandria, Va.,

and that the marshal shall deliver him safely into the

hands of Eliza Bethune, who was appointed Tom's

Committee by the Supreme Court of New York, and also

that General Bethune pay over $7,000 to the order of Court

for the credit of Blind Tom as his earnings. |

The New York Times reported on August 18, 1887 that Tom had arrived in New

York and was again living at 7 St. Mark's Place, where he had lived for

seven years with John G. Bethune. The change in custody appeared to be a

smooth one, because Wiggins opened an engagement at Association Hall in

New York City on September 26, 1887. Southall reports that by the

following year Wiggins was again composing music for publication as well:

|

Mrs. Bethune was also getting some monetary rewards

from Tom's creative talents given the 1888 copyright dates

on three works published by the Oliver Ditson Music

Company, namely: his Columbus March, Blind Tom's

Mazurka and When This Cruel War is Over. |

15 Frequent Travel

His new manager added Sunday performances to Wiggins' busy concert

schedule, and for the first time allowed him to appear on the same concert

bill as other musicians. For years after obtaining custody, she was the

defendant in lawsuits seeking $3,000 in unpaid fees due to a prior

attorney. One such suit led to the discosure that by 1892 Eliza Bethune

had married Albrecht Lerche, the attorney who had won her custody of

Wiggins. Together they oversaw a life of near-constant travel and

performances for him.

16 $15 for Mother

In October of 1900 a reporter named W. C. Woodall interviewed Charity

Wiggins for a paper in Columbus, Georgia, the Columbus Enquirer, which

published a picture of her in front of the home in which she was living.

Southall writes:

|

According to Woodall, Tom's mother was living with one of

her daughters and in good health. The writer found it an interesting fact that "of the many thousands of dollars

made through the genius of her blind son, she had

received a comparatively small amount." He reported that

she had recently received "fifteen dollars from the

manager of Blind Tom, which the humble household appreciated."

At the time of the interview several of Tom's siblings were

living in Columbus as cooks, washer women and day

laborers at 50 cents a day; one of them was a church

janitor.

At the time of the interview Tom's mother had not seen her

son for many years and seemed to "deeply resent the separation." She said

"they stole him (Tom) from me.

When I was in New York I signed away my rights."

According to the December 26, 1902, Professional World, Tom's mother died in Alabama and was buried in

Columbus, Georgia; she was 105 years old. |

17 John Davis CD

The pianist John Davis recorded the first commercial CD of music composed

by Thomas Wiggins, John Davis Plays Blind Tom, Newport Classic

85660 (1999).

The CD's titles are:

Cyclone Galop (6:12)

The Rainstorm (4:29)

Sewing Song: Imitation of a Sewing Machine (7:01)

Battle of Manassas (7:50)

Improvisation on "When This Cruel War Is Over" (7:21)

Wellenklänge - Voice of the Waves (6:41)

Oliver Galop (1:12)

Virginia Polka (3:04)

Water in the Moonlight (3:00)

Grand March Resurrection (4:49)

Vivo Galop (2:06)

Daylight (4:06)

March Timpani (5:53)

Reve Charmant - Nocturne (6:47)

Davis writes in the liner notes:

|

Eventually, Blind Tom's repertoire grew to an astounding

seven thousand established works, including those of Bach,

Beethoven, Chopin, Mendelssohn, and Liszt, not to mention

over a hundred composed by himself. |

Davis stresses that these and other compositions of Wiggins "...employ a

host of uniquely evocative images..." from Nature, musical instruments and

machinery.

18 Death

Prof. Southall reports that Tom's last public appearances appear to have

been those of April 17-22, 1905 in Boston. She adds that the Boston

Evening Transcript left no doubt in its subsequent review that the famed

pianist was "still celebrated" at the conclusion of his long career.

Little was heard of him in the following two years. He died on June 13,

1908. The author gives the cause of death and the funeral arrangements:

|

Although he died at age 59 of cerebral apoplexy at the

home of Mrs. Eliza Bethune Lerche in Hoboken, New

Jersey, where he lived for several years, his body was

taken to the funeral chapel of Frank E. Campbell Company

in New York. |

Lengthy obituaries appeared in newspapers around the country, but it was

generally left to Black newspapers to point out that Thomas Wiggins, this

marvelously gifted pianist and composer, was exploited all his life. They

lamented that first slave owners and then managers reaped riches from

Tom's talents while Tom lived and died penniless, and while his mother and

siblings lived in poverty.

19 Dr. Oliver Sacks

The liner notes of John Davis Plays Blind Tom include an essay by the

noted neurologist and author Oliver Sacks. It is excerpted from the

doctor's book An Anthropologist on Mars: Seven Paradoxical Tales, first

published in 1995 by Alfred A. Knopf and released in paperback the

following year by Vintage Books USA. Dr. Sacks explains autism and his

belief that Wiggins was an autistic savant. He first repeats contemporary

accounts of Tom's playing of the piano, including his unusual movements

and expressions, before observing:

|

Although Tom was usually called an idiot or imbecile, such

posturing and stereotypies are more characteristic of

autism - but autism was only identified in the 1940s and

was not a term, or even a concept, in the 1860s.

Autism, clearly, is a condition that has always existed,

affecting occasional individuals in every period and

culture.

It was medically described, almost simultaneously, in the

1940s, by both Leo Kanner in Baltimore and Hans Asperger

in Vienna. Both of them, independently, named it

"autism."

Both emphasized "aloneness," mental aloneness, as the

cardinal feature of autism; this, indeed, was why they

called it autism.

Singular talents, usually emerging at a very early age and

developing with startling speed, appear in about 10

percent of the autistic (and in a smaller number of the

retarded - though many savants are both autistic and

retarded). |

20 Hush

In 2002 an Atlanta theater company, 7 Stages, presented

the world premiere of a play entitled Hush: Composing Blind Tom Wiggins.

The author is Robert Earl Price, a member of the theater company. Wendell

Brock reviewed it for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution on Feb. 6, 2002:

|

The Verdict: The most important Atlanta stage production

of the new century, it demands that we look at, and listen

to, the legacy of Blind Tom Wiggins.

After being shunted away for nearly a century,

Blind Tom Wiggins - the Georgia-born slave and

19th century piano savant - is back.

Directed by 7 Stages artistic director Del Hamilton,

using

Davis' recorded music and starring the astonishingly gifted Anthony Tatmon as Tom, "Hush" is a celebration of the

fecund imagination of Price and the haunting compositions

of Wiggins.

Tatmon plays up Blind Tom's idiosyncracies, the

fractured

speech, the tricks of mimicry and memory, his character's

grotesqueries. But to his credit, he also makes his

character human - and humorous (Tom hates butter beans,

he says "cabbage stinks," but he loves cake). Tatmon

gives a brilliant, startling and unsettling performance.

It's harrowing to see Tom nearly fed to the hogs as a

baby,

to see his father (Neal Hazard) almost get his foot hacked

off because he has the "running-away sickness" and to

hear his mother (Shontell Thrash) recount the way her boy

spoke her name so tenderly ("Maa-muh"). Her answer was

always: Hush.

|

The intial run of Hush in the home theater

of 7 Stages was just the beginning for the work. An article in TransatlanticJournal.com in 2004 tells of subsequent performances both

on tour and at the Martin Luther King Historical Site:

|

HUSH: Composing Blind Tom Wiggins remains one of 7

Stages' most recent and beloved highlights, returning to

the 7 Stages mainstage a year after its world premiere by

popular demand and touring throughout the region. It

appeared as part of the Alliance Theatre's City Series as

well as, in abridged form, at the Martin Luther King

Historical Site throughout the summer of 2003. |

21 Works

Prof. Dominique-René de Lerma

Collection:

Plantation melodies as sung by Blind Tom, with his

original accompaniments, for voice & piano. n.p.: T[homas?]

G[reene?] Bethune, 1881. 1. Waggin’ up Zion's hill; 2.

That welcome day; 3. Come along, Moses; 4. Them golden slippers.

Specimens of Blind Tom's vocal compositions. n.p.:

c1867. 4 p. I wish dear Jodie would come home; The man who

mashed his hand; The man who snatched the cornet out of his

hand; ; The man who sprained his knee; Mother, wilt thou come

and cure me?. Text: Blind Tom. Library: Library

of Congress.

Individual titles:

CD: William Brown, tenor; Ann Sears, piano. Albany TROY

(1999; Fi-yer!; A century of African-American song).

Academy schottische, for piano. n.p.: W. P.

Howard, 1864.

Amazon march, for piano.

Blind Tom's march, for piano. Boston: Oliver

Ditson, 1851.

----- Boston: Oliver Ditson, 1860. Dedication: Mary Bethune.

Also published in 1883?

----- Boston: Oliver Ditson, 1888. 5p. Library: Library of

Congress.

----- Chicago: S. Brainard's Sons, 1894. 12p. Library: Library

of Congress.

----- New York: S. Brainard's Sons, 1913. 11p. Library: Library

of Congress.

Blind Tom's mazurka, for piano, by J. C. Beckel

[pseud.], rev. by L.K. Boston: Oliver Ditson, 1888. 5p. Library:

Library of Congress.

Blind Tom's waltz, op. 2, for piano. Philadelphia:

J. Marsh, 1865. 5p. Library: Library of Congress.

----- Boston: Oliver Ditson, 1888, rev. by L. K. 5p.

Library: Library of Congress.

----- Boston: Oliver Ditson, 1892. 5p. Library: Library of

Congress.

Cascades, for piano.

Columbus march, for piano, rev. by L. K. Boston:

Oliver Ditson, 1888. 5p. Library: Library of Congress.

Concert hall polka, for piano. Boston: Oliver

Ditson, 1888.

Concert Waltzer, for piano (1882).

AC: Geneva H. Southall, piano. Challenge Productions CP-8206

(1982).

Cyclone galop, for piano (ca. 1887). New York:

William E. Ashmall, 1887. 7p. Duration: 6:12. Library: Library

of Congress.

CD: John Davis, piano. Newport Classics LC 8554 (1999, John

Davis plays Blind Tom).

Daylight; a musical expression, for piano (1866).

Chicago: Root & Cady, 1866. 5p. Dedication: H. L. Benham.

Library: Library of Congress.

----- Chicago: S. Brainard's Sons, 1866.

AC: Geneva H. Southall, piano. Challenge Productions CP-8206

(1982).

CD: John Davis, piano. Newport Classics LC 8554 (1999, John

Davis plays Blind Tom).

Delta Kappa march, for piano (by 1880).

General Howard’s march, for piano. Philadelphia:

J. M. March, 1865.

General Ripley's march, for piano.

Grand march de concert, for piano.

Grand march resurrection, for piano (by 1901).

Highlands NJ: I. Bethune; Boston: Oliver Ditson, 1901. 5p.

Duration: 4:49. Library: Library of Congress.

CD: John Davis, piano. Newport Classics LC 8554 (1999, John

Davis plays Blind Tom).

----- New York: F. Blume, 1887. 11p. Library: Library of

Congress.

March timpani, for piano (1880), by Prof. W. F.

Raymond [pseud.]. New York: F. Blume, 1880. 11p. Dedication:

Joseph Poznanski. Duration: 5:53.

----- New York: F. Blume, 1887. 11p. Library: Library of

Congress.

AC: Geneva H. Southall, piano. Challenge Productions CP-8206

(1982).

CD: John Davis, piano. Newport Classics LC 8554 (1999, John

Davis plays Blind Tom).

March lanpier polka, for piano. New York: F.

Bllume, 1887.

Masonic grand march, for piano.

Military march, for piano or organ, by C. T.

Messengale [pseud.]. Bucyrus OH: Guckert Music, 1889. 9p.

Library: Library of Congress.

Oliver galop, for piano (1859). Boston: Oliver

Ditson, 1860. Duration: 1:12. Library: Library of Congress.

----- New York: H. Waters, 1860. 4p. Library: Library of

Congress.

CD: John Davis, piano. Newport Classics LC 8554 (1999, John

Davis plays Blind Tom).

LP: Alan Mandel, piano. Desto 6445/7 (1975).

LP: Ruth Norman, piano. Opus One 39 (ca. 1978).

Rêve charmant; nocturne, for piano (1881). New

York: J. G. Bethune, 1881. Library: Library of Congress.

----- Boston: Oliver Ditson, 1888. 10p. Dedication: William

Steinway. Duration: 6:47.

AC: Geneva H. Southall, piano. Challenge Productions CP-8206

(1982).

CD: John Davis, piano. Newport Classics LC 8554 (1999, John

Davis plays Blind Tom).

Sewing song; imitation of the sewing machine, for

piano (1888). New York: William A. Pond, 1888. 11p. Duration:

7:01. Library: Library of Congress.

AC: Geneva H. Southall, piano. Challenge Productions CP-8206

(1982).

CD: John Davis, piano. Newport Classics LC 8554 (1999, John

Davis plays Blind Tom).

Symphony based on Blind Tom's theme, for piano.

New York: Cosmopolitan Music, 1973.

That welcome day, for voice & piano. [n.p.?] 1881.

AC: Oral Moses, bass; Ann Sears, piano. (Art songs and

spirituals by Black Americans).

The battle of Manassas, for piano (1866). Chicago:

Root & Cady, 1866. 11p. Duration: 7:50. Library: Library of

Congress.

----- Chapel Hill: Hinshaw Music (Piano music in 19th century

America, ed. by Maurice Hinson).

----- Cleveland: S. Brainard's Sons, 1884. 11p. Library: Library

of Congress.

----- New York: Brainard & Son, 1913, ed. by de Roode.

CD: John Davis, piano. Newport Classics LC 8554 (1999, John

Davis plays Blind Tom).

LP: E. Power Biggs, organ (Fisk Organ, Old West Church,

Boston).Columbia M-34129 (Two centuries of heroic music in

America, 1976) [abbreviated].

The man who got the cinder in his eye, for medium

voice & piano. Cleveland: Root and Cady, 1866.

The music box, for piano.

The music boy Bounjo, for piano.

AC: Geneva Southall, piano. Challenge Productions CP-8206 (1982)

The rainstorm, op. 6, for piano (1854). New York:

J. L. Peters, 1865.

----- Boston: Oliver Ditson, 1892, 1888. Rev. by L. K. Duration:

4:29. Library: Library of Congress.

AC: Geneva Southall, piano. Challenge Productions CP-8206 (1982)

\.

CD: John Davis, piano. Newport Classics LC 8554 (1999, John

Davis plays Blind Tom).

The reaper, for piano (after 1865). Dedicated to

one of Gen. Bethune’s daughters.

Virginia polka, by Tom, the blind Negro boy pianist, only

10 years old, for piano. (1860). New York: Horace

Waters, 1860. 4p. Dedicated: Miss Martha McCon Reese, of Georgia

[a daughter of Gen. Bethune?]. Library: Duke, Library of

Congress, Spingarn.

----- Boston: Oliver Ditson, 1860. Library: Library of Congress.

AC: Geneva Southall, piano. Challenge Productions CP-8206 (1982)

CD: John Davis, piano. Newport Classics LC 8554 (1999, John

Davis plays Blind Tom).

Vivo galop, for piano (1865). Duration: 2:06.

CD: John Davis, piano. Newport Classics LC 8554 (1999, John

Davis plays Blind Tom).

Water in the moonlight, for piano (1854). Chicago:

S. Brainard’s Sons, 1866. 5p. Duration: 3:00. Library: Library

of Congress.

----- n.p.?: Oliver Ditson, 1866.

AC: Geneva Southall, piano. Challenge Productions CP-8206 (1982)

CD: John Davis, piano. Newport Classics LC 8554 (1999, John

Davis plays Blind Tom).

Wellenklänge; Concert Waltzer; voices of the waves,

for piano (1882), by François Sexalise [pseud.]. New York: J. G.

Bethune, 1882. Duration: 6:44. Library: Library of Congress.

----- New York: Spear and Dehnkott, 1887. 16p. Library: Library

of Congress.

AC: Geneva Southall, piano. Challenge Productions CP-8206 (1982)

CD: John Davis, piano. Newport Classics LC 8554 (1999, John

Davis plays Blind Tom).

When this cruel war is over; variations, for

piano, rev. by L. K.(1865). Philadelphia: J. Marsh, 1865.

Duration: 7:21.

----- Boston: Oliver Ditson, 1888. 11p. Library: Library of

Congress.

CD: John Davis, piano. Newport Classics LC 8554 (1999, John

Davis plays Blind Tom).

Wilt thou bring my baby home, for medium voice &

piano (1881). n.p.: J. G. Bethune, 1881. 5p. Text: Blind Tom.

Library: Library of Congress.

AC: Oral Moses, bass; Ann Sears, piano. (Art songs and

spirituals by Black Americans).

VHS: Blind Tom. Chicago: Clearvue (M4BVH V221). Duration:

30:00.

22 Bibliography

Prof. Dominique-René de Lerma

“Black Tom” by P., from the Springfield Republican, in

Dwight’s journal of music, v22n9, n556 (1862/11/29) p275.

“Blind Tom (and done with)” in Dwight’s journal of music,

v22n10, n557 (1862/XII/06) p286.

“Blind Tom again” in Dwight’s journal of music, v22n7,

n553 (1862/XI/15) p267-268. [The authors of these four letters

are identified a “F.M.R., a lady,” “Benda,” “Montgomery,” and

“W.”]

“Blind Tom, the musical prodigy” in All the year round,

v8 (18??), p126.

“Blind Tom” in Atlantic monthly, v10 (1962/XI) p580-585.

“Blind Tom” in Dwight’s journal of music, v22n6, n553

(18761/XI) p250-252. [followed with comments by Dwight, p254.]

“Book uncovers how Black musical genius Blind Tom was exploited

in 1880s” in Jet (1980/!/17) p30.

“Extraordinary people” in New York times (2000/II/5).

“General James N. Bethune, owner of Blind Tom, was outstanding

personality in Columbus” in Columbus magazine

(1941/V/31).

“More about Tom” in Dwight’s journal of music, v22n10,

n557 (1862/XII/06) p283.

“The remarkable case of the late Blind Tom; How an imbecile

blind Negro pianist amazed scientists and musicians the world

over” in Etude, v26n8 (1908/VIII) p532.

“Thomas Green (Blind Tom)” in Jet, v64 (1983/V/30) p24.

“Thomas Green Bethune” in A salute to historic Blacks in the

arts. Chicago: Empack Publishing Co., 1996, p16-17.

“Tom, the blind pianist” in Harpers weekly (1866/II/10).

Abbott, Eugenie B. “The miraculous case of Blind Tom: The enigma

of the famous musical genius who astonished the world” in

Etude, v58 (1940/VIII) p517-564.

Abbott, Lynn. Out of sight; The rise of African American

popular music, 1889-1895, by Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff. [n.p.]:

University Press of Mississippi, 2002.

Abdul-Rahim, Raoul. Blacks in classical music; A personal

history. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1977.

American music v4n1, p51

Anderson, Florence. “Blind Tom’s music” in Cincinnati

enquirer (1965/VII/26).

Andreu, Enrique. “Tragedia de un Beethoven negro” in Revista

musical chilena, v3n25-26 (1947/X-XI) p24-29.

Bakers 1992

Becket, James A. “Blind Tom as he is to-day” by John A’Becket,

in Ladies’ home journal, v15n10 (1898/IX) p13-14.

Reprinted in Black perspective in music, v4n2 (1976/VII)

p184-188.

Berry, Lemuel, Jr. Biographical dictionary of Black musicians

and music educators, vol. 1. Guthrie OK: Educational Book

Publishers, 1978.

Bettonville, Albert. “En 1860, Blind Tom était l’ancêtre des

pianistes de jazz” in Hot club magazine, v26 (1948/IV)

p7-8.

Bio-bibliographic index 1972

Black music research bulletin v12n2, p14

Black music research journal, 1980, p9, 85, 86, 90 (Wiggins);

1981-1982, p128, 138 (Bethune); v9n2, p228; v10n1, p154 (Bethune)

Black perspective in music, v2n1, p159; v4n2, p161, 172;

v5n2, p241; v7n1, p104; v14n1, p9; v14n2, p192.

Blind Tom, the great Negro pianist. Baltimore: 1867.

Brawley 1937

Brawley, Benjamin. The Negro genius. New York: Biblo &

Tannen, 1968, p121-133.

Brooks, Tilford. America’s Black musical heritage.

Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1984.

Brooks, Wendell. “Lyrical Hush celebrates work of Blind

Tom Wiggins” in Atlanta journal (2002/II/6) pE3.

Carter, Madison H. An annotated catalogue of composers of

African ancestry. New York: Vantage Press, 1986.

Cole, Aaron. “The true story of Blind Tom” in Daily mail

[Freetown, Sierra Leone]; 1955/VI/29)

Coleman, Kenneth, ed. “Blind Tom” in Dictionary of Georgia

biography, ed. by Kenneth Coleman and Charles Stephen Gurr.

Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1983.

Complete catalogue of sheet music and musical works.

Board of Music Trade of the United States of America, 1871.

Corrothers, James D. “Blind Tom, singing” in Black

perspective in music, v4n2 (1976/VII) p189-190. Reprinted

from Southern workman, v30n5 (1901/V) p258-259. [poetry]

Cotter 1959

Cuney-Hare, Maud. Negro musicians and their music,

introduction by Josephine Harreld Love. New York: G. K.

Hall, 1996, 1936. Xl, xii, 439p. (African-American women

writers, 1910-1940, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., general editor).

LC 96-17696.

Davis, J. Frank. “Blind Tom” in Human life (1908/IX).

Davis, Rebecca Blaine Harding. “Blind Tom” in Atlantic

monthly, v10 (1862) p580-585. Reprinted in Dwight’s

journal of music, v22 (1862) p250-252.

Derricotte, Elise P. Word pictures of great Negroes.

Washington: Associated Publishers, 1964, p13-21.

Dienhart, Paul. “Blind Tom uncovers exploitation of a

Black musical genius” in Minneapolis spokesman (1979/XII/27).

Dienhart, Paul. “Southall uncovered story of Blind Tom” in

Report (1980/I) p4-5.

Eason, Charissa-Marie. “Biography reveals untold story of Blind

Tom” in Minnesota daily, v81n93 (1980/I/17) p10.

Elson, Louis C. The history of American music. New York:

Macmillan, 1904.

F. H. Parmelees musical monthly, n13. New London: (1885/VI),

p4.

Fisher, Renée S. Musical prodigies; Masters at an early age.

New York: Association Press, 1973, p69-72.

Floyd, Samuel A., Jr. Black music biography; An annotated

bibliography, by Samuel A. Floyd, Jr., and Marsha Reisser.

White Plains: Kraus International Publications, 1986., ppxxiii,

44, 46-47

Greene, Frank. Composers on record; an index to biographical

informatrion on 14,000 composers whose music has been recorded.

Metuchen: Scarecrow Press, 1985. 636p. OSBN 0-8108-1816-7. (entry:

Bethune Greene)

Hampton 1970

Hughes, Langston. Black magic; A pictorial history of the

Negro in American entertainment. Englewood Cliffs:

Prentice-Hall, 1967.

Hunt, Inez. “The story of Blind Tom” in The baton of Phi Beta,

v51n3 (1972) p6-7.

Index to the Schomburg clipping file. Alexandria:

Chadwyck-Healey, 1986.

Jablonski, Edward. The encyclopedia of American music.

Garden City: Doubleday & Co., 1981, p62

Jackson 1985a, p88, 94

Jay, Ricky. Learned pigs and fireproof women. New York:

Villard Books, 1986, p74-81.

Juhn, Kurt. “Black Beethoven” in Negro digest (1945/VI)

p33-38.

Kech, George R., ed. Studies in nineteenth-century

Afro-American music, ed. by George R. Keck and Sherrill V.

Martin. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1988.

Kehler, George. The piano in concert. Metuchen: Scarecrow

Press, 1983.

King, Anita. “Blind Tom; a child out of time” in Essence

(1973/VIII).

Krummel, Donald W. Resources of American music history,

by D. W. Krummel, Jean Geil, and Deane L. Root. Urbana:

University of Illinois Press, 1981.

Lerma, Dominique-René de. “A concordance of music entries in

five encyclopedias: Bakers, Ewen, Groves, MGG, and Rich” in

Black music research journal 1981/1982, p127-150. Reprinted

in Black perspective in music, v11n2 (1983/fall)

p190-209.

Lerma, Dominique-René de. Black music in our culture;

Curricular ideas on the subjects, materials, and problems.

Kent: Kent State University Press, 1970.

Lerma, Dominique-René de. Reflections on Afro-American music.

Kent: Kent State University Press, 1972.

Lyle 1984 (c1850-)

Magill, Charles T. “Blind Tom, unresolved problem in musical

history” in Chicago defender (1922/VIII/19).

Mapp, Edward. Directory of Blacks in the performing arts.

Metuchen: Scarecrow Press, 1978., 1990 (1849-)

Nixon, Louise Emerson. “Blind Tom: incredible imitator” in

Music journal, v29n8 (1971/X) p40, 61.

Oliver 1990

Ortiz 1955

Patterson 1988, p479

Pfaelzer, Jean. “Domesticity and the discourse of slavery; ‘John

Lamar’ and ‘Blind Tom’ by Rebecca Harding Davis” in Esq; A

journal of the American renaissance, v38n1 (1992) p31-56.

Reed, Bill. Hot from Harlem; profiles in classic

African-American entertainment. Los Angeles: Cellar Door

Books, 1998. 292p. LC 97-094657; ISBN 0-9661449-0-2

Riis, Thomas. “The cultivated White traditions and Black music

in nineteenth-century America; a discussion of some articles in

J.S. Dwight’s journal of music” in Black perspective

in music, v4n2 (1976/VII) p156-176.

Roach, Hildred. Black American music, past and present.

Boston: Crescendo, 1973.

Robinson, Norbonne T. N., Jr. “Blind Tom, musical prodigy” in

Georgia historical quarterly, v51 (1967) p336-358.

Robinson, Wilhelmena S. Historical Afro-American biographies.

Washington: Associated Publishers, 1976, p51 (International

library of Afro-American life and history).

Rogers 1947, p558

Sampson, Henry T. Blacks in blackface; A source book on early

Black musical shows. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press, 1980., p1.

Sears, Ann. “Bethune, Thomas Greene Wiggins (“Blind Tom”)” in

International dictionary of Black composers, ed by Samuel A.

Floyd, Jr. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1999, v1, p105-108.

Sears, Ann. “Keyboard music by nineteenth-century Afro-American

composers”in Feel the spirit; Studies in nineteenth-century

Afro-American music, ed. by George R. Keck and Sherrill V.

Martin. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1988, p135-155.

Seguin, Edouard. Idiocy and its treatment by the

psychological method. 1866.

Simmons, William J. Men of mark; Eminent, progressive, and

rising. Chicago: Johnson Publishing Co., 1970, 1887,

p557-560.

Slonimsky, Nicolas. “Bethune, Thomas Greene” in Baker’s

biographical dictionary of musicians. 6th ed. New York:

Schirmer Books, 1978, p165-166.

Songs; Sketch of the lide, Blind Tom, The marvelous musical

prodigy, the Negro boy pianist, testimonials and opinions of the

most eminent composers. Philadelphia: Ledger Book and Job

Printing, 1865.

Southall, Geneva Handy. “Bethune (Green), Thomas “ in The new

Grove dictionary of American music, ed. by H. Wiley

Hitchcock and Stanley Sadie. London: Macmillan, 1986, v1,

p203-204.

Southall, Geneva Handy. “Bethune, Thomas Greene” in

Dictionary of American Negro biography, ed. by Rayford W.

Logan and Michael R. Winston. New York: W. W. Norton, 1982,

p43-44.

Southall, Geneva Handy. “Bethune, Thomas” in The new Grove

dictionary of music and musicians, ed by Stanley Sadie.

London: Macmillan, 1980, v2, p663-664.

Southall, Geneva Handy. “Blind Tom; A misrepresented and

neglected composer-pianist” in Black perspective in music,

v3n2 (May 1975) p141-159.

Southall, Geneva Handy. Blind Tom, the Black pianist-composer

(1849-1908) continually enslaved, intro. by Dominique-René

de Lerma. Lanham MD: Scarecrow Press, 1999. xvii, 214p. ISBN

0-8108-3594-0 (hardback); 0-8108-4545-8, paperback, 224p..

Southall, Geneva Handy. Blind Tom; The post-Civil War

enslavement of a Black musical genius, intro. by Samuel A.

Floyd, Jr. Minneapolis: Challenge Production, 1979. xix, 108p.

LC 79-54227.

Southall, Geneva Handy. The continuing enslavement of Blind

Tom, the Black pianist-composer (1865-1887), book II, intro.

by T. J. Anderson. Minneapolis: Challenge Productions, 1983.

xiii, 318p. LC 79-54227.

Southern 1971a

Southern 1971b

Southern, Eileen. “Bethune, Thomas Greene” in Biographical

dictionary of Afro-American and African musicians. Westport:

Greenwood Press, 1982, p33-34. (The Greenwood encyclopedia of

Black music).

Southern, Eileen. “Thomas Greene Bethune, 1849-1908” in Black

perspective in music, v4n2 (1976/VI) p177-183.

Southern, Eileen. The music of Black Americans; A history.

2nd ed. New York: W. W. Norton, 1983,.

Spencer 1991

Spradling, Mary Mace. In black and white; Afro-Americans in

print. 3rd ed. supplement. Detroit: Gale Research, 1985.

Detroit: Gale Research, 1980. (entries: Bethune, and Wiggins)

Stoddard, Tom. “Blind Tom, slave genius” in Storyville,

n28 (1970/IV-V) p134-138.

Stoutamore, Albert Lucian. Music of the old South, colony to

confederacy. Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson

University Press, 1972. 349p. LC 74-149827. ISBN 0-8386-7910-2.

Thomas 1989, p95

Thornton, Ella Mae “The strange case of Blind Tom” in Music

journal, v15 (1957/XI-XII) p16.

Thornton, Ella Mae. “The mystery of Blind Tom” in Georgia

review, v15 (1961) p394-400.

Thornton, Ella Mae. “The strange case of Blind Tom” in Music

journal, v15 (1957/XI) p91-92.

Toll, Robert. Blacking up; The minstrel show in

nineteenth-century America. New York: Oxford University

Press, 1974, p197.

Treffert, Darold. Extraordinary people; Understanding idiots

savants. New York: Harper & Row, 1989.

Treffert, Daryle. Extraordinary people; Redefining the idiot

savant. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

Trotter, James M. Music and some highly musical people.

Chicago: Afro-Am Press, 1969, 1878, p140-159.

Tutein, Anna Amalie. “The phenomenon of Blind Tom” in Etude,

v37 (1918/II) p91-92.

Wiesel, H. J. “Blind Tom” in Dwight’s journal of music,

v22n17, n564 (1863/01/24) p340-341.

Winston, Michael R., ed. Dictionary of Negro biography,

ed. by Michael R. Winston and Rayford W. Logan. New York: W. W.

Norton, 1982.

Woodall, W. C. “Blind Tom as seen by his mother, Charity Wiggins”

in Sunny south (1900/X).

Woodall, W. C. “Blind Tom, our most famous personage” in

Columbus magazine (1941/VII/31).

Wright, Josephine. “Thomas Greene Bethune (1849-1908)” by

Josephine Wright and Eileen Southern, in Black perspective in

music, v4n2 (1976/VII) p177-183.

Young, George. Le merveilleux prodige musical, Tom l’Aveugle,

le jeune nègre pianiste d’Amérique don’t les récentes

répresentations dans les salles de Saint-James & Egyptian à

Londres ont fait grande sensation; Tuteur de Tom l’Aveugle, M.

W. P. Howard, abrégé de la vie, témoinages des musiciens et

savants, opinions de la presse anglaise & américiane, tradut de

l’anglais par Edward Stebbing. Paris: Imprimerie Vollée,

1867. 37p.

Young, George. The marvelous musical prodigy, Blind Tom, the

Negro boy pianist whose performances at the great St. James and

Egyptian halls, London, and Salle Herz, Paris, have created such

a profound sensation; Anecdotes, songs, sketches of the life,

testimonials of musicians and savans, and opinions of the

American and English press of Blind Tom. New York: French &

Wheat, 1868. 30p. LC 43-20016.

---- Baltimore: The Sun Book and Job Printing Establishment,

1878. 30p.

---- Liverpool: Benson & Holme, 1867. 54p.

----- New York: French & Wheat, 1867. 30p.

----- New York: French & Wheat, 1868. 30p. LC 43-20016.

---- New York: French & Wheat, 1870. 30p.

This page was last updated on

March 5, 2022

|